Manipulation Inc. – The Rise of Corporate Propaganda

Public relations professionals have always been in the business of persuasion. Whether they're polishing a company's image, managing a crisis, or promoting a political candidate, the objective remains clear: shape public perception. But where does persuasion cross the ethical line into propaganda? It's a blurry boundary that, in recent years, seems increasingly fragile.

The roots of public relations are not entirely innocent. Edward Bernays, often called the father of PR, openly embraced the term "propaganda," using psychology to manipulate public opinion. In his influential 1928 book, aptly named "Propaganda," Bernays argued that controlling public attitudes was not just possible - it was necessary. He famously stated that "those who manipulate this unseen mechanism constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power." While PR has since tried to distance itself from the dark connotations of "propaganda," the uncomfortable link still lingers beneath the industry's glossy surface.

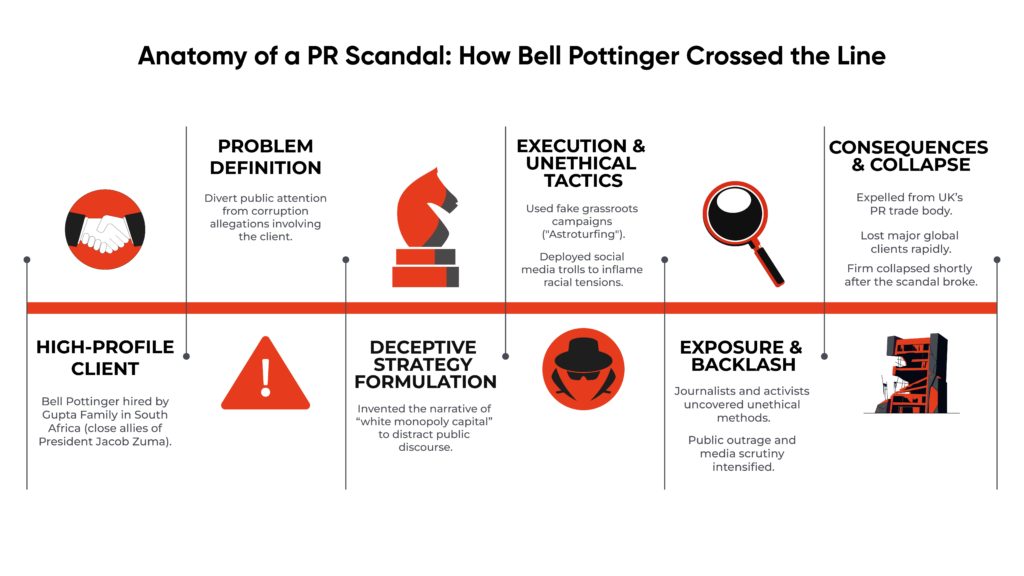

Take, for instance, the infamous case of the British PR giant Bell Pottinger. Once considered among the most prestigious firms in the industry, Bell Pottinger dramatically imploded in 2017 after a disastrous campaign in South Africa. Hired by the Gupta family, who had close ties to then-President Jacob Zuma, Bell Pottinger orchestrated a campaign designed to divert public anger over corruption allegations by fabricating a false narrative around "white monopoly capital." The firm went so far as to deploy social media trolls and fake grassroots activism to inflame racial tensions and distract public attention from its clients' scandals. When journalists and activists exposed the truth, Bell Pottinger faced fierce backlash, was expelled from the UK's PR trade association, and soon after collapsed entirely.

This wasn't Bell Pottinger's first questionable campaign. Earlier, they had been secretly paid more than $500 million by the Pentagon to run covert propaganda in Iraq. The PR firm once openly boasted of mastering the "dark arts" of communication, further muddying the distinction between legitimate PR and outright Soviet-style propaganda. For many PR professionals, Bell Pottinger's downfall was a stark reminder of how quickly ethical boundaries can vanish under pressure.

It's not only rogue firms crossing the line. Corporate giants can be guilty of questionable PR tactics too. A notable scandal emerged in 2011 when Facebook (META) secretly hired the respected firm Burson-Marsteller to plant negative stories about Google. The firm approached journalists anonymously, urging them to report on privacy concerns surrounding Google's products. Once uncovered, the scheme sparked widespread outrage, leading Burson-Marsteller to admit they had publicly breached their own ethical standards. This covert operation highlighted how easily reputable organizations could slip into unethical territory, turning competition into propaganda warfare.

The tactics of disinformation have evolved rapidly, leveraging digital platforms and social media to blur the line between authentic communication and deceptive propaganda. What makes these tactics so dangerous - and effective - is their subtlety. Rather than blatant falsehoods, modern digital-era propaganda often involves carefully distorted truths or exaggerated narratives that resonate emotionally, making them harder to combat. PR professionals find themselves battling an environment where genuine communication risks getting drowned out by sophisticated multi-level disinformation campaigns. In this digital age, distinguishing between authentic and artificial content has become increasingly challenging.

This erosion of trust isn't limited to the political realm. Corporate communications, too, are often viewed skeptically by the general public, who are tired of being manipulated. Surveys consistently show declining public trust in institutions - governments, corporations, and media - mainly because of widespread cynicism toward their messaging. Phrases like "we apologize for any inconvenience" or "based on current information" are frequently read as evasions or half-truths rather than genuine attempts at transparency.

The solution isn't simple, but it starts with PR professionals holding themselves and their peers accountable. Industry standards clearly outline principles of honesty, transparency, and integrity. Yet the ethical practice isn't simply following written codes - it's about consistently choosing transparency over spin, honesty over evasion, as emphasized in industry guidelines like the PRSA Code of Ethics, even when transparency is uncomfortable.

The PR industry needs a renewed commitment to integrity, actively rejecting practices that blur into propaganda. Practitioners must educate clients about the long-term risks of deceptive tactics, emphasizing that credibility, once lost, is incredibly difficult to rebuild. Leaders in PR should openly debate these ethical dilemmas, setting clearer boundaries before technology and tactics evolve even further.

Ultimately, PR practitioners aren't propagandists by nature. They play an essential role in a healthy, informed society by fostering dialogue and transparency. Yet the line that separates responsible persuasion from manipulative propaganda remains fragile. Recognizing this boundary and vigilantly safeguarding it is vital - not just for the reputation of public relations but for the trust on which our society depends.